Washington Week full episode for September 11, 2020

9/11/2020 | 25m 14sVideo has Closed Captions

Washington Week full episode for September 11, 2020

Washington Week full episode for September 11, 2020

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Major funding for “Washington Week with The Atlantic” is provided by Consumer Cellular, Otsuka, Kaiser Permanente, the Yuen Foundation, and the Corporation for Public Broadcasting.

Washington Week full episode for September 11, 2020

9/11/2020 | 25m 14sVideo has Closed Captions

Washington Week full episode for September 11, 2020

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch Washington Week with The Atlantic

Washington Week with The Atlantic is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

10 big stories Washington Week covered

Washington Week came on the air February 23, 1967. In the 50 years that followed, we covered a lot of history-making events. Read up on 10 of the biggest stories Washington Week covered in its first 50 years.Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipROBERT COSTA: What the president knew and when he knew it.

PRESIDENT DONALD TRUMP: (From video.)

I wanted to always play it down.

COSTA: The president tells Bob Woodward that he knew the coronavirus was deadly and airborne in February, and sparks a firestorm.

FORMER VICE PRESIDENT JOSEPH BIDEN: (From video.)

It's disgusting.

We waved a white flag.

He walked away.

He didn't do a damn thing.

Think about it.

COSTA: It is the latest explosive book in this campaign season and comes amid a new whistleblower report.

Will the president pay a price?

Next.

ANNOUNCER: This is Washington Week.

Once again, from Washington, moderator Robert Costa.

COSTA: Good evening.

The title of Bob Woodward's new book, Rage, comes from an interview Woodward and I conducted with the then-candidate Donald Trump in 2016.

Mr. Trump told us, quote, "I do bring rage out.

I always have."

Woodward told me later that the quote was revealing and mattered.

It showed how Trump sees himself.

And the president's critics, they certainly raged this week when they learned what President Trump told Woodward about the coronavirus in February.

Will the president pay a political price with American voters?

It's hard for any reporter to say, but this time there are tapes.

PRESIDENT DONALD TRUMP: (From video.)

You just breathe the air and that's how it's passed.

And so that's a very tricky one.

That's a very delicate one.

It's also more deadly than your - you know, even your strenuous flus.

This is deadly stuff.

COSTA: The president told Woodward on February 7th that he fully understood the threat, but he said this just weeks later to the American people.

PRESIDENT DONALD TRUMP: (From video.)

It's going to disappear one day.

It's like a miracle, it will disappear.

And from our shores we've - you know, it could get worse before it gets better, could maybe go away.

We'll see what happens.

COSTA: And he told Woodward in March that he deliberately played it down.

PRESIDENT DONALD TRUMP: (From video.)

I wanted to - I wanted to always play it down.

I still like playing it down because I don't want to create a panic.

COSTA: Democrats are appalled and say the president lied to Americans.

HOUSE SPEAKER NANCY PELOSI (D-CA): (From video.)

The fact that the president knew, he'd been saying for a long time the whole thing was a hoax.

His delay, denial, and distortion of what was happening has caused many deaths.

COSTA: But the president has dismissed the criticism.

PRESIDENT DONALD TRUMP: (From video.)

They wanted me to come out and scream people are dying, we're dying.

No, no, we did it just the right way.

We have to be calm.

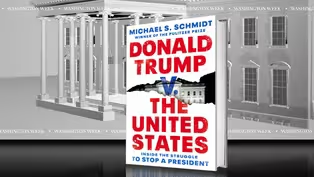

COSTA: Joining us tonight are three of Washington's top reporters: Asma Khalid, political correspondent for National Public Radio; Ashley Parker, White House reporter for The Washington Post; and Michael Schmidt, Washington correspondent for The New York Times and author of Donald Trump Versus the United States: Inside the Struggle to Stop a President.

Ashley, let's begin with you.

You've been reporting in recent days on the fallout of the Woodward book.

Why does that February 7th remark by the president matter?

What was he doing at that time?

What was he not saying to the American public?

ASHLEY PARKER: Right, the question is really what he wasn't doing and what he wasn't saying, and it's a fascinating about 10-day window from - which Woodward recounts in his book - from when Robert O'Brien goes into the Oval Office and tells the president the coronavirus is going to be the biggest national security crisis of your presidency to when Trump tells Bob Woodward - he conveys to him that he understands the severity, that he understands that it is deadly, it is tricky, and that it is airborne.

In that period he really does not convey that grim reality to the American public in words for starters so they can begin preparing and figure out if they need masks and if they have members of their family with co-morbidities and what steps they should be taking to protect themselves.

And if you look at how he spends that time - for instance, the night he gets that warning from Robert O'Brien he goes and he holds a rally in Wildwood, New Jersey.

That weekend he gets on his plane as they are just starting up the coronavirus taskforce, Air Force One, and he flies down to Mar-a-Lago, where he spends both days of the weekend golfing.

That Sunday is Super Bowl Sunday and he hosts a Super Bowl bash at Mar-a-Lago in West Palm Beach.

And so you really see a president who in both action and words was not taking the steps you would expect a responsible leader to take to warn their citizens of a coming deadly pandemic.

COSTA: Mike, Ashley referenced a conversation - a briefing the president had from Robert O'Brien, the national security adviser, in late January of 2020.

In your own book you paint a portrait of this president dealing with advisors during crises, sometimes listening to them, sometimes ignoring them.

When you hear the Woodward tapes and his reporting and compare notes in a sense, what does this all reveal about President Trump and his use of power?

MICHAEL SCHMIDT: Well, I think that what it shows is that the president has been completely sort of unshackled here in the last two years of his presidency.

In the first two years he had folks like John Kelly, he had folks like Don McGahn that were there, that were containers.

But Trump had found a way to hollow those folks out, and that left him in a place where he was even more free to do what he wanted and he didn't have someone like Kelly there who was running the day-to-day operations in the White House like the general that he was.

And what this shows, you see this in his decision to sit down with Woodward and talk to Woodward, in his approach to the coronavirus, in his approach to everything, that the president still doesn't seem to understand the consequences of different things in Washington.

He thought he could charm Woodward and that talking to him would be beneficial to himself.

At times, it looks like he thought he could talk the coronavirus away from the American people and downplay it, and that things would be better.

And here we are coming to the end of the fourth year of his presidency and it doesn't seem like the president has evolved much.

COSTA: Asma, you've done a lot of reporting for National Public Radio about voters in those key swing states of Wisconsin and Pennsylvania and Michigan.

You've also focused on independent voters who may be tracking the president's conduct on the pandemic.

We've had so many controversies during the Trump presidency.

Does this break through with those voters in those states?

ASMA KHALID: You know, honestly, I think that is the key question that we're going to be following up on in the weeks ahead.

What I will say is that, you know, you can look at the tracking polls of how the president has handled the coronavirus pandemic, and what I'm stuck by is you can go back to a point in say early April where the president's general approval rating broadly amongst the American public was hovering right around 50 percent.

He's now, you know, viewed as, I believe - I checked it earlier today - it was, like, less than 40 percent of the public believes that he's handling the pandemic correctly.

And when you look at where those numbers have dropped off, they've dropped off among Democrats and they've also dropped off some amongst independents.

I have been texting with a bunch of voters that I've met, you know, earlier on this summer in some of these key battlegrounds - you know, battleground counties, and one gentleman I talked to earlier today, I thought what was interesting is he is a Republican, but he messaged me back earlier today and said I feel less confident in voting for Trump today than when we spoke earlier this summer.

He's really not sure what to do.

He is very nervous that a vote for Joe Biden would plummet the economy and he is a small-business owner.

And so, you know, that goes back to the president's inability, though, to actually talk about an issue in which he does seem to have an apparent strength with voters, and that's the economy.

The pandemic has not been a strength for him, as we've seen for months and months, and that's what most voters are talking about right now.

COSTA: What a snapshot of this campaign.

All of us reporters are doing our best, Asma texting with voters.

We're doing our best to connect.

Ashley, you're also reporting on the Trump presidency and the economy, and this week the Senate GOP failed to pass its so-called skinny bill, $500 billion coronavirus relief bill.

And as we stay on this pandemic topic, it's not just about the Woodward book, it's also about what will Washington do.

Does the failure of the Senate Republican bill mean that President Trump will finally step into the negotiations, or are talks essentially dead between now and the election?

PARKER: That's a great question, and it's one even before Senate Republicans failed to pass this much more slimmed-down version of a bill that people were putting to the president fairly directly, which was that one of his selling points was that he claimed to be a dealmaker and a businessman, and someone who wasn't particularly ideological, and who would get down and dirty and cut deals with the Democrats.

And so far, we simply have not seen that in about the past year or so.

And some of that is the president's sort of deep-seated anger and frustration toward Speaker Pelosi for impeaching him, frankly.

And the president has basically said as much earlier this week or last week, that he doesn't really feel like he can go out and negotiate with Chuck Schumer and Nancy Pelosi.

Now, again, could that change?

Potentially.

The president changes his mind sometimes based on the hour or on the day.

But right now, the outlook for something getting through both chambers of Congress is not particularly good right now.

COSTA: Asma, one of the revealing moments for me this week as a reporter is watching Vice President Biden on Wednesday speaking - to follow up on Ashley's point about the economy and coronavirus relief.

He responded briefly to the Woodward book, but then he gave his full economic speech in Michigan.

What is the Biden pitch now on the economy?

And what's their closing message at this point?

KHALID: Yeah, I will say my connection's a little poor, but I think you were asking me what the Biden closing economic message is - is that right?

COSTA: It is, correct.

KHALID: OK, great.

So in a nutshell, what he has been emphasizing quite a bit has been this made in America vision.

It might sound - and some Republican Trump base voters will say that it is a reiteration, in their view, of the make America great again policies that President Trump was promoting.

But, look, it's different, to some degree.

I mean, it is a largely manufacturing-based policy that he's been focusing on.

And, you know, he was out there in Michigan, a state that Democrats lost in 2016, touting the need to have more manufacturing jobs here in the United States, but also specifically spelling out policies that he believes would help that - whether it's a 10 percent tax penalty for companies that are offshoring, or whether it's a 10 percent tax credit, he says, for companies that bring some of this manufacturing back to the United States.

You know, what I'm struck by, though, is the degree to which Democrats - this, you know, being the Democratic nominee himself - is talking about the need to offshore manufacturing.

And this is a different economic conversation than Democrats had been having in some previous cycles.

COSTA: Mike, Congress may be stalled when it comes to coronavirus negotiations, but they're investigating - at least in the House - this whistleblower complaint that inside the Department of Homeland Security an official is claiming that he and others have been told to ignore Russian interference in this election and focus on interference and activity by Iran and China.

And so I don't want to forget that issue of interference.

And what's the importance, in your view as a reporter, of this whistleblower report?

SCHMIDT: Well, it's just another example of how either the intelligence community or the law enforcement world has been tilted in the president's direction.

Institutions mimic the people that run them.

And the president has made himself incredibly clear on what he thinks of Russian interference, what he thinks of 2016, and how he doesn't think it's a problem here.

You have to remember, and as I laid out in the book, 2016 was the greatest intelligence failure since September 11th of 2001.

And the federal government has not taken nearly enough measures to have a different footing coming into another election.

So not only are we at a similar or maybe even worse footing than we were in 2016, but at the same time there are now accusations that the federal government, the intelligence part of the government, is skewing the information it has to downplay that threat.

So we're coming at it with the same if not worse tools, and disinformation with our own government about a potential disinformation campaign.

COSTA: When you step back from all of this that we're talking about - Woodward and the pandemic, interference, a whistleblower report - it's clear we're covering a campaign that is tight, based on the latest polls.

And there is a national racial reckoning still unfolding alongside of it.

Here is a quick taste of the latest pitches from both of the contenders.

PRESIDENT DONALD TRUMP: (From video.)

If Biden wins, China wins.

If Biden wins, the mob wins.

If Biden wins, the rioters, anarchists, arsonists, and flag-burners win.

They want to shut down auto production, delay the vaccine.

They want to destroy your suburbs.

They want to erase your borders and indoctrinate your children with poisonous anti-American lies in our schools.

(Boos.)

Not going to happen.

FORMER VICE PREISDENT JOSEPH BIDEN: (From video.)

He used that dog whistle on race.

Now it's a bullhorn.

People don't want a handout.

They just want a fighting chance.

Just give me a shot.

COSTA: Asma, how is the Biden campaign handling that drumbeat from the president on the suburbs, his appeals to White voters?

KHALID: You know, they have certainly been campaigning and trying to reach out to suburban voters.

But what I've been struck by with the Biden campaign - you know, we were talking earlier about the Woodward book.

There are certainly passages in that book that get to, you know, how the president feels about race, how the president feels about Black voters, about White privilege.

Those passages are not really what we've been hearing much about from the Biden campaign.

They have strictly focused on the pandemic.

Biden feels like that has been a dereliction of duty, he says, on how the president's handled the situation.

And so while I say - will say that the president certainly feels very comfortable in talking about racial issues and cultural issues, however you want to define them, what I've been struck by is that, you know, the Biden campaign does not seem to want to engage as much in this conversation.

You know, no doubt he went to Kenosha.

He is certainly dealing with some of these issues in that way.

But I would say, by and large I have been struck by how much they seem to want to center the conversation consistently around the pandemic, and how they feel that the president had not been handling the situation correctly.

COSTA: Ashley, beyond the issues of policing and violence and the suburbs, we're thinking now as reporters about a possible October surprise.

And the president has teased maybe a claim, a statement, an announcement on a possible vaccine.

What have you learned about what he's going to do in terms of an announcement or handling a vaccine in the coming weeks?

PARKER: Well, my reporting shows that the vaccine is the key thing that the president is focused on and has been focused on for a number of weeks when it comes to the coronavirus.

He is laser-like focused on the vaccine, and not that much else.

It's worth noting that, in fairness to the Trump administration, Operation Warp Speed, which is what they call the race for the vaccine, is one of the few things that is going fairly well.

A couple of vaccines are in phase three trials.

It's proceeding along.

And there is a belief that there may be a vaccine ready if not quite on President Trump's timetable - he has said November 1st.

That's, of course, two days before the election.

He said maybe as early as October.

There are trusted people, public health officials in his administration, who say there could be a vaccine ready by the end of the year, or early 2021.

But it seems certain that whether or not there is literally an, you know, injectable into arms vaccine ready, the president is going to tease the promise of a vaccine no matter what.

One challenge that doctors and public health experts, who I was just talking to today, are worried about, is because of who the president is, because this is a president who misleads, and obfuscates, and, frankly, lies sometimes, that there's a huge portion of the population who will not trust this vaccine.

Not the typical sliver of anti-vaxxers, but a much broader swath of the American public who just does not trust President Trump, and a vaccine that he, by his own admission, is rushing through.

So that might be a little wrinkle in whatever surprise the president is trying to roll out.

COSTA: And, Mike, another possible October surprise is John Durham's probe, the investigation of the Russia investigation.

The Hartford Courant reported today that an aide, an official within that investigation resigned.

This entire Durham probe has a cloud of possible pressure from the attorney general over it.

What are you learning on this fluid story about when it's going to be released, the report, and whether it's going to be seen widely as credible?

SCHMIDT: The president wants it released before election day, and he wants more indictments to come out of it besides the one of an FBI lawyer that's happened so far.

He has said this publicly.

He has said it privately.

He has put the pressure on his attorney general here to do that.

But because the president and the attorney general have talked so much about this investigation, there is a strong perception that there is some sort of there there, and that they are going to be turning up some sort of bad information.

The other problem with that, though, is that it undermines the actual investigation, because it shows that the people who are in charge of it are saying that there may be a predetermined outcome.

The president took pains in recent days to say he's not being briefed on it, but the White House chief of staff, Meadows, he talked the other day as if he had intimate knowledge about it, and now here the top lieutenant of this investigation is apparently quitting because they were afraid of the political consequences.

And this is - this investigation has been built up so much on the right that if there is not some sort of there there and some real nugget for them to bite into from this they're going to be severely disappointed.

COSTA: Asma, how is the Biden campaign preparing for the Durham probe, if at all?

And also, how are they preparing to campaign in the final weeks?

You see the president holding rallies once again, yet the Biden campaign is not doing that.

KHALID: Sorry, I think I heard the - I apologize, my connection's not very good.

I think you were asking me about how the Biden campaign is going to be campaigning in the final weeks?

COSTA: Yes.

KHALID: Yes, OK, so I apologize about that, that I couldn't hear correctly.

But in a nutshell, you know, I've actually been looking in quite a bit this week.

I was doing some reporting on the wide-scale discrepancy between the sort of traditional ground-game operation that you have between Republicans and Democrats.

And this isn't just between Biden and Trump; this is between, you know, state Democratic parties and state Republican parties.

And I think what's notable is that you now have a situation where both candidates are physically traveling - both men were in Pennsylvania today, they'll both be in Minnesota next week - but the way that they are campaigning is so fundamentally different.

You know, I mentioned I was in Wisconsin with Joe Biden the other day and he held this small back-to-school event that was in a supporter's backyard with just three people in attendance, a handful of pooled press, and that was it, and it's just - it's so different both in sort of tenor and tone and energy than many of Donald Trump's events.

And so I think what to me is really notable is that, you know, the scale of the events that Joe Biden is holding is fundamentally different, and I do have questions about, you know, if you fly into, say, a key battleground community and you have a small-scale event in someone's backyard and you do a couple of local interviews, is that sufficient to generate the kind of, you know, maybe news buzz that they feel they need?

But in addition to that, they are not, you know, knocking on doors, and the Republican Party claims that every week they are knocking on a million doors.

And I, you know, hear that from state party chairmen on both Republican and Democratic sides, that there is a difference in how they are campaigning.

Democrats are largely campaigning and organizing a ground game that is exclusively via text, phone, and Zoom at this point, and there are big questions about whether or not that is sufficient to mobilize voters and get them out to the polls, and it's a sort of untested theory.

COSTA: Ashley, when you hear all that and you look at the Trump campaign and its own schedule, you look at the president releasing an updated list of Supreme Court nominees this week, do you sense urgency in the president's circle about where he is in the polls, about the need to get back on the road and to have these rallies?

PARKER: Yes and no.

The releasing the list of the Supreme Court potential nominees was something that was absolutely crucial for him in 2016 in reassuring conservatives that he was one of them and that he wouldn't just get into office and revert back to sort of his previous ways, as a lot of them viewed him, a Manhattan liberal.

So that felt like something they were going to do either way.

It worked in 2016.

It is still important to conservatives, the Court.

And it's a savvy move by the president, they believe, to win over and/or reassure this base.

In terms of him sort of gliding back into the rallies without ever really announcing them, one function that serves is this is a president who despite everything we talked about at the beginning of the show, knowing that this is a deadly pandemic, really just wants it to go away.

He sort of wishes he could tweet it away, nickname it away, imagine it away.

Of course, approaching almost 200,000 dead we now know that's not - and kind of always knew, frankly - that's not how this works.

But in doing these rallies, for an evening or for a couple of hours the president is able to create his own false reality where people are not socially distanced, where many people are not wearing masks, where it feels like the coronavirus does not exist.

Just the other night his campaign aides tracked down a New York Times reporter who was sort of taking photos - who was taking photos and saying that people weren't wearing masks, and so it does serve this energizing purpose for the president to pretend the virus isn't there, but of course these rallies we'll find out in about two weeks from now could very well be super-spreader events.

COSTA: Well, we're going to have to leave it there, my friends.

There's so much to talk about these weeks sometimes - explosive books from Mike, from Woodward, from everybody, it's almost too much, but we'll keep on it.

Asma Khalid, Ashley Parker, and Michael Schmidt, really appreciate your time on this Friday night.

And make sure to check out our Washington Week Bookshelf series on our Extra.

It'll be a one-on-one discussion with Michael about his terrific new book.

Find it tonight and this weekend on our social media and on our website.

And before we go, we remember those who died on 9/11 19 years on.

It's a solemn moment every year, and the campaign took a pause on Friday as the president spoke in Pennsylvania and the vice president and former vice president touched elbows at the World Trade Center; great photo.

I'm Robert Costa.

Good night from Washington.

Washington Week Extra for September 11, 2020

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: 9/11/2020 | 18m 42s | Washington Week Extra for September 11, 2020 (18m 42s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipSupport for PBS provided by:

Major funding for “Washington Week with The Atlantic” is provided by Consumer Cellular, Otsuka, Kaiser Permanente, the Yuen Foundation, and the Corporation for Public Broadcasting.